When people talk about math, usually what comes up is a rigidity and order to how things are supposed to go. However, mathematicians have for years uncovered and written about situations that don't make logical sense, and tried to figure out how they can be resolved. While there are thousands of paradoxes from A (Abelson's Paradox) to Z (Zeno's Paradox), this will only cover 4 paradoxes and their solutions. (for more paradoxes, explore this list on Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_paradoxes)

Without further ado, here they are!

1. Achilles and the Tortoise

The great warrior Achilles is challenged to a race 100 meter long by a Tortoise. Knowing of Achilles' speed, the Tortoise asks for a 10 meter head start. Achilles tells the Tortoise that the head start will be nothing, as he can run 10 meters in a second. The Tortoise responds that, in the time it takes Achilles to run 10 meters, it will have run 1 meter. When Achilles runs that meter, the Tortoise will have run .1 meters. When Achilles runs .1 meters, the Tortoise will have run .01 meters. Thus, Achilles will seemingly never be able to catch the Tortoise despite being much faster.

Achilles, will of course, be able to catch the Tortoise. The paradox can be resolved by thinking about it one of two ways:

- The distance between them gets smaller by a factor of 10. The distance between the two will be decreased by a factor of 10 infinitely many times in theory, so the distance between them will eventually equal zero. At this point, Achilles and the tortoise will be next to each other, and Achilles will pass the Tortoise.

- Let Achilles' speed be 10 and the Tortoise's speed be 1. At time t, Achilles' position will be 10t and the Tortoise's will be t+10. These positions will be equal when 9t=10. After this time, Achilles will be ahead of the Tortoise. What will their position be? 11.11111...

2. The Boy or Girl Paradox

You're visiting a couple of statisticians who have two children. You know neither of the children's genders. After you knock on the door, a man arrives at the door, with his son poking his head around the corner. What is the probability that the other child is a boy as well, assuming that the probability of a child being a boy is 50% and being a girl is 50%?

It might seem fairly straightforward, given that there's a 50% probability of a child being a boy. However, we have to remember that there are 2 children total. View the problem from the perspective of knowing neither of the children's genders. There are 4 possibilities for the genders of the kids, with the oldest child having their gender listed first: MM, MF, FM, and FF. These probabilities are all equal. Having seen that one child is a boy, we can only eliminate the final option as a possibility. Thus, the three possibilities for the children are MM, MF, and FM. These all have equal probabilities, so the probability that the other child is a boy is equal to one third.

3. The Potato Paradox

Let's say you have a 100 pound bag of potatoes. 99% of the weight of potatoes is water. You decide to let your bag of potatoes dehydrate until the weight of the bag is only 98% water. After doing this, you're astonished that your bag of potatoes now weighs 50 pounds!

How does making water a slightly smaller percentage of the weight change the weight so dramatically? We know that the original bag was 99% weight by water, so this means that 1 pound of the weight came from the 'solid' part of the potatoes. Thus, after dehydration, 1 pound of solid accounts for 2% of the weight of the bag. We can thus solve for x, where x is the weight of the bag, for 1 = .02x. Thus, x = 50 pounds.

4. The St. Petersburg Paradox

While you're walking one night, a friend approaches you with a fair coin and asks to play a game. They tell you that they will give you $2 if it lands on heads once, $4 if it lands on heads twice in a row, $8 if it lands on heads three times in a row, $16 if it lands on heads four times in a row, and so on and so forth. The game will end as soon as the coin lands on tails. After explaining the rules, your friend asks you if you want to wager $100 to play the game. Being a mathematician, you decide to calculate whether or not this would be reasonable. After doing the math, you quickly pull out a $100 bill and ask to play.

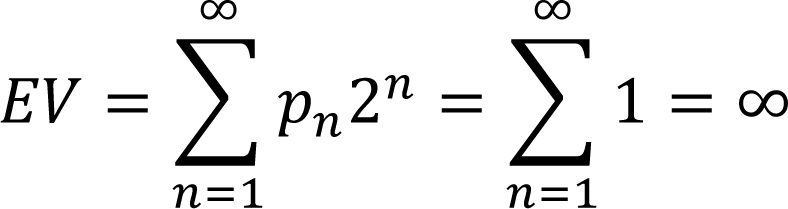

Why would you do this? The formula for expected value suggests that this is a smart idea. The formula for expected value is:

E = P(A)*A + P(B)*B +P(C)*C + ....

We plug in the probabilities of the coins landing on consecutive heads and the value you'll be given to find:

E= 0.5*2 + 0.25*4 + .125*8 + ... = 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + ....

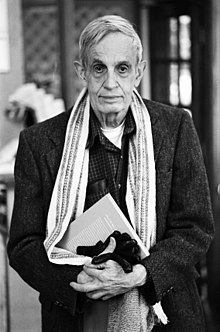

This value will be infinite. While at face value there doesn't appear to be a solution to resolve the paradox, economists and mathematicians have worked on an equation that gives a finite result to this equation - making it more in line with the thinking that one wouldn't bet everything on a game where earning everything back would be very unlikely!

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/134574190-56a59d905f9b58b7d0dda814.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-609150939-908610fc8796472caea29b93f5bf7a9f.jpg)